What is it We're Looking For?

A couple of years ago, I fell completely and totally in love with tennis. Not playing it (yet), but watching it. For years I'd wanted to get into tennis because so many of my friends loved it, but – this is not a joke – every year at the end of the summer when everyone was watching the US Open I'd say to myself, oh shit. I forgot to get into tennis again.

I have never been much of a sports person. As a kid I tried to get into football (the American variety) when the small Colorado town we'd moved to was gripped by Denver Bronco-mania. I remember going to a neighbor's house to watch Elway lead the Broncos in their second-ever Super Bowl appearance, proudly wearing my little orange and blue t-shirt with my hair in two long braids. The game was long and boring. The Broncos lost. The next year, I tried watching again, albeit with less anticipation and enthusiasm. The Broncos lost. Two years later when they went again, I was like, absolutely not. I gave up on football forever.

(They lost.)

It didn't help that I wasn't very good at team sports when I was younger. Partly because I wasn't good at the sports themselves, and partly because I wasn't comfortable with the whole team thing. By the time team sports were an extracurricular activity at school, the only things I had in common with John Elway were that we'd both been pretty popular and that we'd suffered an incredibly public defeat. Only mine was at the hands of another girl who moved to town and somehow convinced my friends I was a geek who they shouldn't be friends with. Since most of them were the good volleyball players in town, the writing was on the wall.

So I guess it makes sense that, between my two extremely 1980s teen movie-esque traumas, team sports and I were not meant to be.

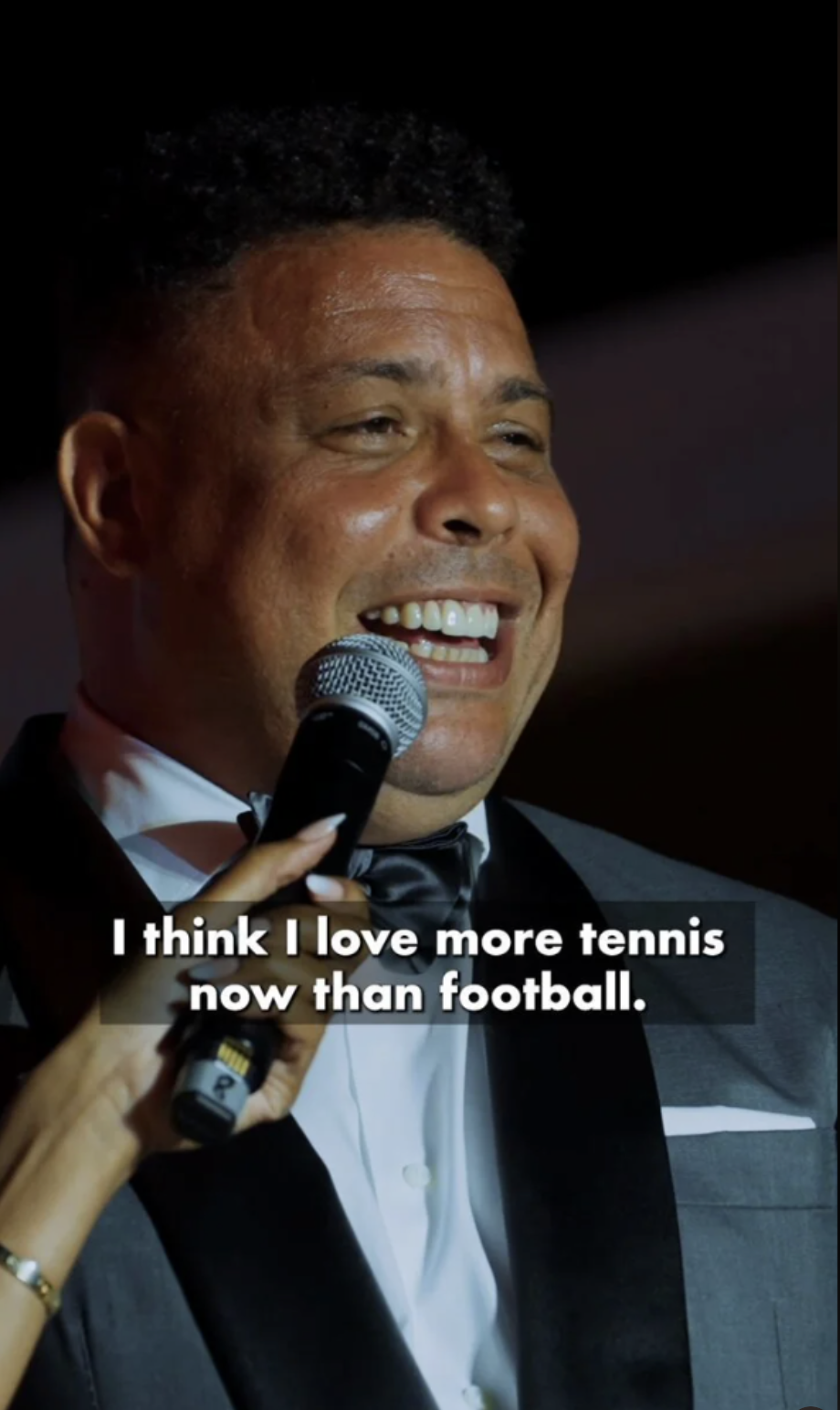

Anyway, I don't come from a serious sports family. I don't remember watching a game with my Brooklyn Dodger-loving (and only the Brooklyn Dodgers) dad until the 2000 Subway Series, when I sat with him as he recuperated from surgery and taught me about baseball. I'd fallen for soccer two years earlier, during the 1998 World Cup, thanks to my English and European coworkers. While I've watched every World Cup since, that first experience remains so formative that my favorite player is still Ronaldo O Fenômeno.

But I never really got bitten by the sports bug. Sure, I was up at an ungodly hour to watch a devastating USA loss to Germany in 2002 (say what you will about US men's soccer but that was a great match). Sure, I went to major league baseball games, professional basketball games, even one college football game (well, half of one). And sure, like almost everyone in America that year, I watched the 2001 World Series, desperately cheering for the Yankees in the aftermath of 9/11. Beyond that though? You would never catch me watching sports by myself. It was always with someone else who knew and cared infinitely more.

And then tennis came along.

The stupid thing about my tennis obsession is that it began in 2021, which means I missed almost the entirety of the Williams Sisters and Big Three (+ Andy) eras. I showed up in time to watch most of them retire. The first time I ever watched Djokovic play was when he lost to Medvedev in the US Open men's final. It was only the second match I'd watched in my life, too. The first was the day before, at Arthur Ashe in Flushing, when Emma Raducanu went on her improbable run to win the women's US Open after starting the tournament in the qualifying rounds.

A grand slam final is a hell of a first match to see live. I was there because a friend of mine had invited me to go with her. A few years before when I was living in Stockholm, that friend – then someone I'd only just met but immediately liked – had been in town for work. I last-minute invited her to come to my birthday dinner once I realized she'd be in town that night and had no plans. I remember her being surprised (in a good way) at the invitation – that I would ask a new acquaintance to something like a birthday dinner, that I'd find a way to get the small restaurant to accommodate one more chair at a crowded table, that I so enthusiastically wanted her to come even though we barely knew each other. It was so much fun to have her there, as I knew it would be, and it cemented our friendship.

I don't think it's a coincidence that I fell for tennis when I did or the way I did. If anything, I think it's an absolutely perfect example of human connection and discovery. It's full of serendipity and unorthodox ways of engaging with the world, but it's also a long process, something that clicks when all the pieces fall into place.

At Spotify and at Instagram, I worked on some different projects related to discovery. I never worked on the algorithms – although I do have thoughts on algorithms and on whether you actually hate them, which I'll save for another day – so I wasn't responsible for what you saw, when, or why. But I explored discovery in the contexts of music, podcasts, visual content, interests, etc. It taught me a lot about people's relationships to discovery as a behavior, as well as how discovery happens in a more qualitative, real world sense. More and more I think this human mode of discovery gets lost in a sea of metrics and LLMs and thumbs up Netflix signals, and I wonder why more people don't see it.

One of the key things about discovery is that people have different relationships to it. Not everyone feels the same about discovery. As soon as you read that, you probably went, duh of course everyone knows that, but surprisingly that's not true. I have worked with people who build the products you use all the time and they do not know this. In fact, I think it feels obvious after you read it because suddenly you think about your friends who only ever want to go out for Italian food or the way your dad has four CDs he'll listen to in the car and THAT'S IT. Discovery is sort of a spectrum that's influenced by different factors. On one side of the spectrum is "no thank you, I hate learning about anything other than what I already like, and I will always refuse to do so." This is where adults who are obsessed with Disney and/or Star Wars live (please don't come for me, it's a joke). On the other end of the spectrum are people who are always exploring, always at the vanguard, always looking to find out what's new. In some ways, they almost love the act of discovery as much as all the stuff they find while engaging in it. Between these poles is everyone else, and not necessarily in a static way. Sometimes those other factors make us more or less interested in discovery, like when we're sick of the same playlist we've been listening to, or when we absolutely can only watch that one familiar TV episode we've seen 100 times because our brains cannot handle anything else.

But discovery also happens in different ways, ways that get around even people with the strongest anti-discovery defenses. I think our best discovery experiences are through gradual exposure, even if we don't realize it. We might hear a friend talk about an artist, then see a post about them, then maybe see or hear some of their work without realizing it, and then finally seek them out or be open to a bigger introduction. We don't all spend our lives Columbusing every single new thing we find. In fact, I think that rarely happens. We don't live in vacuum sealed isolation, only to emerge when a friend wants to take us to a new restaurant. We're all constantly marinating in culture whether we want to be or not, and the sights, sounds, flavors will creep in, seasoning our lives in imperceptible ways until we're like, what am I craving something and where can I find it? And then boom.

This is why online discovery can be both a lot fun and absolutely soul crushing. We used to have more pathways to discovery that we could actively engage in, trusted connections and breadcrumb trails we'd follow of our own accord, until we finally Made A Discovery, aka found something we liked and brought it into our own little taste sphere. But then there was just so much stuff everywhere all at once constantly being shoved at us usually when we were not in the mode for discovery and maybe even trying to do something else. Plus all that stuff started to feel the same, all the time, or variations on a theme, which made it feel like the opposite of discovery. Then we started to wonder who all those recommendations were really for: Us or the product itself?

The very last thing I did at Instagram was a deck on a new model for thinking about discovery. When I say "the very last thing I did at Instagram," I mean my manager had me present it to the head of research the day before they laid me off. I didn't take that deck with me because, as I mentioned last week, I only recently became interested in being sued by Meta when I saw what kind of publicity it could generate; before that I was just scared. But the heart of the idea was that human discovery does not look like a lettuce farm, which is how a lot of online discovery is structured. Oh, you like this one thing? Well great, here's an endless row of it, as far as the eye can see. This only works with cute animal videos, and even I, a true connoisseur of cute animal videos, will now only stay on a social media app for a few cute animal videos. I have seen A LOT of them.

Yes, there are people who want discovery in the form of a lettuce farm. Or a tidy garden with neat orderly rows of tulips and no surprises. But a lot of us are looking for discovery is in the form of a perfect overgrown English garden, one that looks wild and organic but that has been tended to carefully. There's a tiny little patch of pink flower here, a sprinkling of it across the way over there, and then suddenly up the path there's a whole burst of bleeding hearts. There's nothing totally linear about it, and if anything there's a deep an interconnected root system, symbiotically keeping everything alive.

Tennis came into my life when I was beginning to approach friendship differently. Sitting way high up in Ashe where I could see the full geometry and proportions of the court, I realized how small the players really are, and how big the court is. More than anything, I realized how truly individual it is. One player, responsible for solving problems on the fly, changing strategy when something isn't working, cheering themselves on. You can see how hard it is to forget the mistake they just made, to stay focused and move on to the next point, and you can see how quickly things unravel when that focus betrays them. So much of tennis is a mental game, from constructing points to identifying and exploiting an opponent's weakness to not absolutely folding under extreme pressure. And a player has to do that for two, three, four, sometimes even five or more hours.

I am far from a tennis expert, and I am certainly not David Foster Wallace (or Brian Phillips), so I'm not going to suddenly start writing all about tennis in this newsletter. But my extremely non-linear path to "discovering" tennis makes me think about how important it is to protect the magic of human discovery. It wasn't just tennis itself that made the eventual discovery special, it was how I discovered it, with whom, and everything that led up to that point. Even all the years and incredible players I missed out on – that gives me a different relationship to this thing I now love. I think when we complain about the way social media and algorithms have "flattened" the world and our exploration of it, we're expressing the loss of those deeper root systems that are buried beneath everything we find and come to love. It's another form of rootlessness, and how do we stop it before the experience erodes even further?

Until next Wednesday.

Lx

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.