Friction is Necessary Resistance

This will likely come as no surprise, but I love a good theory. Scientific theory, philosophical theory, art theory, literary theory: You name it and I'm probably interested in learning about it. I might not agree with it, I might think it's wrong, but I will want to learn more about it. Maybe the only type of theory I don't go for is conspiracy. That's right, Meets Most is a conspiracy theory-free zone. Give me abstract thinking, lots of contemplation, and logical reasoning. Want to spend time with me? Be forewarned that I will say "I have a theory about this" at least once per conversation.

In fact, my fondness for theory is how I ended up getting a PhD in sociology. Fun fact: Before starting my graduate program in sociology, I had never taken a single sociology course in my life. Wild, right? I'd taken a few anthropology classes in undergrad and had done a curious mix of courses for my first master's degree* (I was in the second cohort of a then-new program called Communication, Culture, & Technology at Georgetown, which is fun because it's a literal description of my life's work). But no sociology classes. I only applied for sociology programs because of something a professor said to me, one of the few truly good professors I had over the combined 14 (FOURTEEN) years I spent in college and graduate school. (Side note: This is why I joke that having graduate degrees means only that you're educated, not that you are smart, because no smart person would do this to themselves.) This professor, acknowledging my love of theory while recognizing my need to connect theory to real life, to make it practicable and grounded, suggested I look into something like sociology. He felt sociology was more likely to engage in the theory/praxis overlap than, say, literary theory.

Now, whether sociology was the right subject matter and whether getting a PhD was the right call for me, who can say. These are questions best left for therapy. Either way, I learned some useful things and successfully escaped the lure of purely abstract naval-gaze mental noodling. Then I fled academia and did product work for 15 years, which taught me how to take abstract ideas and make them actionable.

(My time in tech also taught me you cannot shove every single insight into a single slide deck, essay, newsletter, whatever, but that's a topic for later, so put a pin in it.)

A friend who I used to work with and who was a very high-level product lead once told me, "I miss working with you. The value of great user research is that it tells me how to think about a problem. I don't have time to figure out how to think about it. I need you to unlock a new way of thinking about the issue I'm trying to solve and shift my perspective so I can find solutions I would otherwise never have thought of." While this might sound like me tooting my own horn (although who could blame me), that's not why I share it. The point is that change is a two-way street. Insights have to be actionable – and you, the recipient, have to be open to letting someone else change your perspective.

People need to be able to do something with information, especially when there's an absolute firehose spraying information at them 24/7. Insights without action make people frustrated. They start to despair and stop listening. So it's vital to provide not only information but a framework for how to put that information to use. In other words, if you give a man a fish, you feed him for a day. But if you change the way he thinks about the stupid products that are ruining everything, you help him problem-solve for a lifetime.

Which brings us to the topic of friction. Specifically, a type of friction known as "user friction" or "product friction."

For those of you who have never worked in tech or who blessedly do not spend most of your time thinking about it, user friction is pretty simple: It's anything in a product that slows a user down or keeps them from accomplishing a goal. There are lots of useful deep dives into user friction if you'd like to learn more. The tl;dr is:

-

There are three types of friction that affect users:

- Interactive: Do users feel dumb when they try to use the product or is the product intuitive and easy to use

- Cognitive: Do users have to think a lot or perform a lot of actions or does the product reduce cognitive load and make tasks seem easier/more efficient

- Emotional: Do users feel uncertain, unsafe, and hesitant when they use the product or does it make them feel confident and secure

-

Not all friction is bad, and sometimes you want friction to make sure users absorb information or don't take actions they will regret

So far so good, right? When you read these deep dives, you think: Okay, reducing bad friction and adding good friction helps users achieve goals within the product. It sets them up for success on the product. It allows them to avoid making mistakes that might be attributed to the product. It makes them feel more positive about the product. It makes them want to come back and keep using the product. It helps differentiate the product.

Oh.

Now, I'm not going to argue that bad clunky design is better for humans. I am grateful for intuitive, low-friction designs that allow me to do tasks quickly and without wanting to fling my phone or computer into the nearest sea. I feel this deeply every time I open the frustrating and widely-loathed redesigned iPhone Photos app, even though I've been using it for, what, eight months now? But what I am going to argue is that "user friction" isn't only important for product designers. It's something users – as in, all of us – need to think a lot more about.

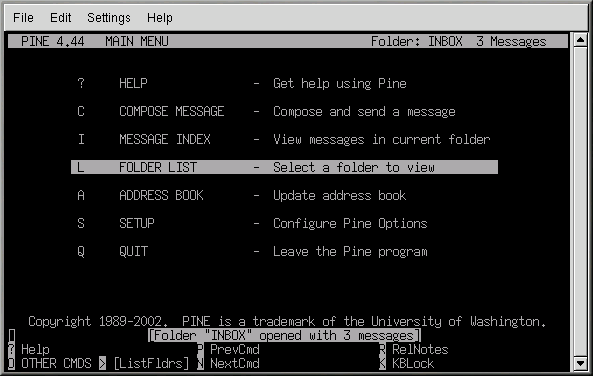

User friction is a helpful way to think about who really benefits from good design. Let me give you an example. When I started using the internet, which was in 1992, there was a lot of user friction. There was no web (well, there was, but not really). Hell, there was no graphical user interface (aka GUI). I had to use Pine for my email and telnet to access chat rooms. I had a clunky desktop PC and a 14.4 kbps dial-up modem. Do you know how slow that connection was, and how often my freshman dorm roommates picked up the phone? Getting online was nothing but friction, but I went online intentionally because I loved it.

Now I am online all the time and I hate it. Worse, I am a 21st Century monster about it. I hate it but also if a website takes fifteen seconds to load I lose my mind. I hate it but also if I can't get good internet service on a sleek little handheld device while riding on the subway I'm annoyed. I hate it but also if I am unable to find a something online I question whether it even exists.

Somewhere between then and now we got trapped. We got used to the ease and speed and efficiency, all the nice thoughtful intuitive "user-centric" reduction in friction. We got so used to it that we lost any resistance we might have had. Even though now we now angrily ask questions like "Is this really about what's best for the user, or is it about what's best for the product and the corporation????" we're still merrily posting away and boosting their metrics and even falling for the same old tricks.

So I've been tinkering with a little theory (see what I did there), which is this: Friction is a form of resistance. I mean this both literally – because that's the definition of friction – and figuratively. The more companies reduce friction within their products, the easier it is for us to capitulate. We do it without even realizing half the time. Sometimes we're forced into it, because these technologies dominate every aspect of our lives and are implemented and controlled by industry leaders who don't have our best interests at heart. It is hard to escape algorithmic choice, disinformation, and harmful technologies when they've cut off and literally disrupted many of the avenues we used to have to engage with each other and the world.

But just like in other frustrating areas of modern life, we still have some control. There are small acts we can all take to try and reintroduce some friction, to resist what feels like the inevitable decline into habits and behaviors we know will come back to haunt us. A while back, while conducting some research at a past job, a participant told me that he – probably like many of you – made an intentional choice to never shop on Amazon. He told me that he did it even though it was inconvenient and even though it had a literal price for him. He had to spend more time and energy to get the things he needed or wanted, and he usually had to spend more money. Even so, all that friction was worth it for him.

I think about this every time I go to look something up online. I search on Google, because it's right there, right in the URL field. It's so easy, I don't even have to think about it. There's no friction. Then when my search results come up, I see all that tantalizing information that's now at the top, and I'm so tempted to use it. To let Google's AI do the work for me, rather than scroll further and put in the... effort? Is it really effort to quickly look at various sites and assess for myself if they're reputable, if the information is what I'm looking for? Is that really so hard or so time consuming? Do you know how long it would have taken any one of those sites to load on a 14.4 kbps modem? Oh my god, what have I become?

So I don't. I don't use the AI summary. I try to hang on to my old habits and not be seduced by this newest frictionless choice. I remind myself even by writing that I should switch to another search engine. That I shouldn't get annoyed when other browsers are slow to load, because I know Google has ways to maximize the experience on Chrome to make you think it's faster, better, easier than the others. That I should make the small effort required to reintroduce friction into my online life before it really is too late.

Stay curious. Every time you use an iPhone or a social media app, every time you go to buy something online, think about how easy it is to click click click and voila, there you are scrolling or spending. Think about the many decisions that have gone into the product itself, decisions that help you feel confident and secure about the actions you have to take and the decisions you make on that platform. Then ask yourself how many decisions have been made that similarly benefit you or the people around you off the platform.

Resistance isn't futile. Resistance simply a little bit of good old fashioned friction.

Until next Wednesday!

Lx

PS: If you want to have a good laugh, here's the master's thesis I wrote on cyborgs and androids in film and literature. When you come back to mock me, please remember that it was 2003. To be honest, pretentious theory bullshit aside, I was a little ahead of my time, which allowed me to continue being ahead of my time with this movie review and this piece on sexbots.

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.