Don't Tweet Back in Anger

When something sets you off, where do you feel it? I don't mean emotionally. I mean: Where do you feel it in your body? Maybe this is a weird question to you, something no one has ever asked you to think about before. Me, I first feel it in the center of my chest, like someone's done a two-fingered one-inch punch right to my sternum. It hurts, it's hot, I can't breathe. Almost immediately the sensation moves back and radiates up and out. My arms and the back of my neck go prickly. I get a little dizzy and it feels as if there's a pressure building that can only escape my body by exploding out my ears and the back of my head. In other words, it's 1944, and I'm a cartoon cat about to lose my shit at a cartoon mouse.

Now, anger is a normal human (or cartoon cat) emotion. It's not weird or bad to feel angry, any more than it's weird or bad to feel any emotion, whether happy or wistful or anxious. Emotions are complicated. Why else do we sometimes find ourselves feeling utterly bereft and alone in the midst of what should be an otherwise joyous event? Hell, the other day I thought about the fact that all our emotions exist inside us all the time, even when we're not actively feeling them. Sometimes the anger comes in, and sometimes it recedes with the tide.

The problem, as you hopefully already know, is not that we feel anger. The problem is that we feel anger when we shouldn't, or maybe that we act on our anger in ways that are not healthy for us or for the people around us. Emotional regulation can be very challenging under the best of circumstances, even when it doesn't feel like society is in a tailspin. On your best day, what happens if something suddenly pisses you off? How are good are you at pausing in that split second and asking yourself: Wait, why am I angry? Is angry the right thing to feel in this moment? If it's not, what's the appropriate emotion here? If it is, what's an appropriate response? How should I act? Should I even act at all? Hey, I guess this is why they call it anger management.

A funny thing about me is that I am actually more comfortable arguing with someone face-to-face than I am arguing on the internet. I don't mean that I've never argued on the internet, or that I've never said something online I immediately regretted and deleted. Absolutely I have. It would be a remarkable achievement to be online as long as I have and not do those things. But I tend to pause much more easily online than I do off, which I think is probably the reverse of most people. I'm more likely to tell you to your face that I think you're being an asshole than I am to do it anonymously on the internet. Wild, I know, but I guess this is why after 25 years of living in California, people there still asked me where I was originally from. (Philadelphia. Obviously.)

Earlier today, when I went on Bluesky and saw something that infuriated me, I sat there looking at it, seething but not responding. I took a screenshot, sent it to a friend, and after a few minutes of feeling hot and light-headed, I also felt calm enough to know that saying anything would be a bad idea. The time had come to log off.

We all know that logging off is healthy. In 2018, I myself – up until that point a very heavy Twitter who at one point deleted eighty thousand (80,000) tweets – once logged off Twitter for two and a half years. It was extraordinary how beneficial that simple act was for my mental health. Even when I technically logged back on in 2020, I never really went back. Not until Bluesky did I sort of get sucked back in to a Twitter-like social network, and some days I almost regret it. But today I was glad I went online and got angry, because it was in the process of pausing and logging off that I did some useful thinking about social media and our current emotional and political landscapes.

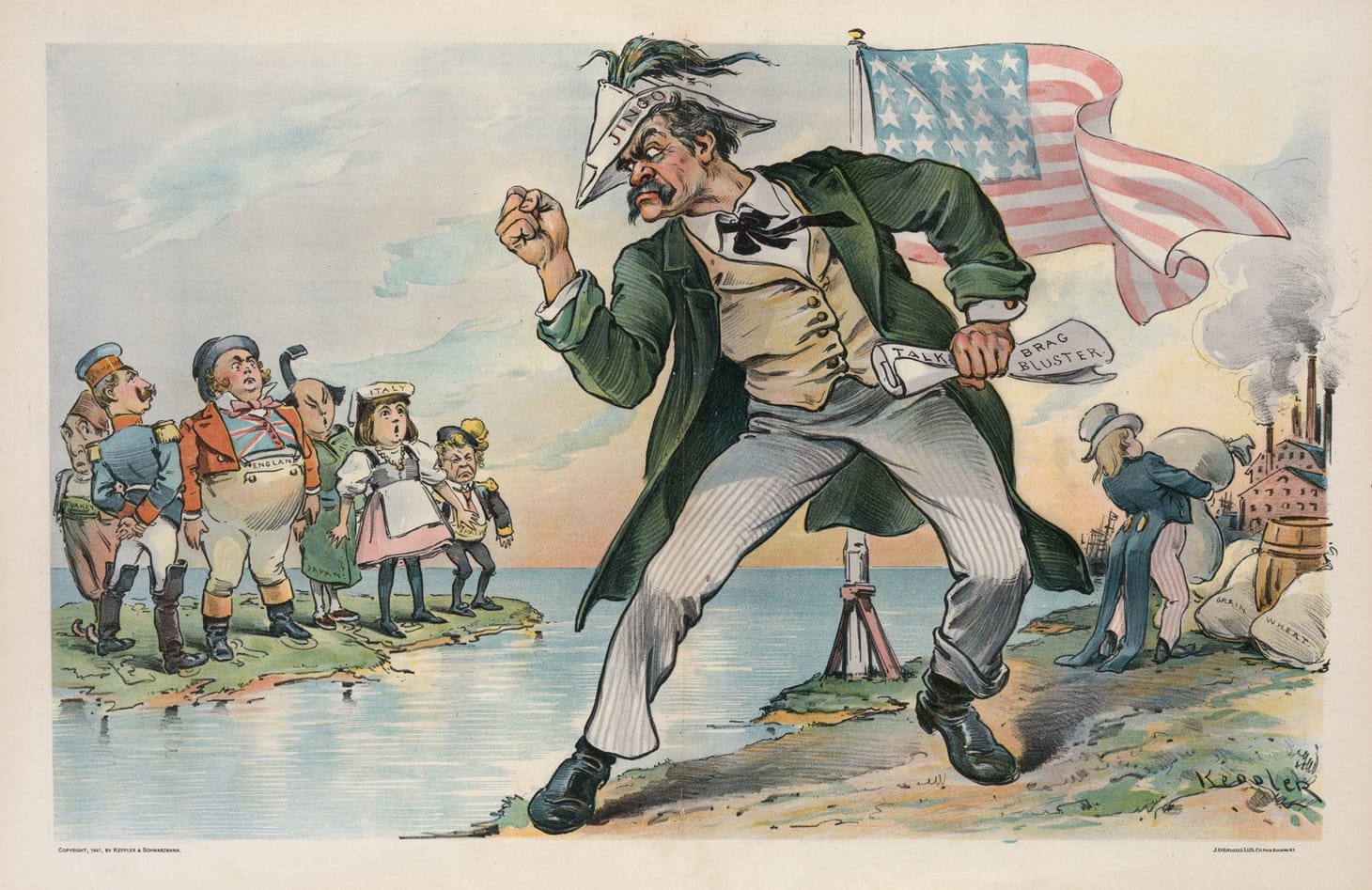

An era such as ours, marked by polarization and division, is not an era in which people engage in a lot of nuance and complexity. It's hard enough to discuss almost any topic when the general vibe is "pick a side, or else." And I don't just mean with hot-button political issues either, but about any and everything. As we have all learned the very hard way, simple, loud, populist messages get the most traction. Big clickbait-y headlines grab attention. We are told to find our brand, find our lane, find niche. Hammering away at a topic in a way that says RIGHT and the other people are WRONG gets you more eyeballs than inviting people to shift their perspectives and complicate their worldviews, and certainly way more eyeballs than asking them whether they might also be contributing to the problem.

It's easy to blame this problem on our old nemesis The Algorithm, as controlled by other other old nemeses, Those Dickheads Who Control The Algorithm. It's not our fault we're so polarized, it's the algorithm. It's not our fault we're trapped in these angry bubbles where we sometimes turn on each other, it's the dickheads who built the platforms that funneled us into these angry bubbles. Blame the binary on binary code! You know what? That's not wrong, necessarily. But it's not the whole picture. And you knew I was going to say this: We're not entirely faultless in all of this, either.

The other day, Charlie Warzel posted that, when he took a multi-day break from Bluesky, where he gets a lot of his news, he was much less aware of the news. He found this really surprising.

Setting aside the obvious issue here – namely that anyone could be surprised by this, let alone someone who writes a column for The Atlantic – I want to focus on the second part, where he says it's a structural issue. I think he means that the real problem isn't how the press covers the news or even what stories it choses to cover, but the fact that – again, I'm not sure how this is an insight – if you don't pay attention to your primary news source, you don't know what's going on in the news. Which, to my understanding, has always been true? Even when people trusted mainstream news outlets, and even when they covered stories we care about? Most people read the paper, watched the news report, maybe listened to the radio. We had more of those outlets than we have now, but that doesn't mean the news was constantly filtering into everyone's lives in some other magical way.

If anything, we have a very different structural problem at hand. It's not just the lack of trustworthy mainstream outlets, or the bubbles and silos we find ourselves in. It's also the delivery mechanism of the news, and in some ways the news itself: A relentless firehose of increasingly atomized information, with no way to modulate or moderate the frequency or intensity of any of it. The news is delivered in exactly the same way as every other piece of information online, whether it's celebrity gossip or a feelgood story about a neighborhood grandma or your friend's graduation or the dismantling of democracy. A collection of tweets, feed posts, comments, videos, longer-form writing, soundbites, podcasts, and photos. Everything is presented in the same way, with the same sense of urgency, on roughly the same platforms. And everyone engaging with all of it in the same ways, with the same senses of urgency, on roughly the same platforms.

Sometimes I like to think about how, as the internet got bigger and bigger, our modes of sharing got smaller and smaller. We made websites, then we blogged, then we wrote feed posts, then finally we condensed everything into either a grid-worthy photo or 240-characters. Obviously these forms weren't sufficient, otherwise we would never have had to endure all those fucking tweet storms and endless Twitter threads. But this has been the problem with all these platforms, and in some ways with the very concept of these platforms themselves – they force us to conform to their constraints. We don't see them as a tool for communication, but as the tool for communication.

When I was at Slack, I put together a couple of documents about some bigger insights I developed beyond the immediate product work at hand. One of those I called The Structure of Information Work, and the other was called Information Overload. Obviously I can't share them here (or at least I don't think I can, since I did the work as a Slack employee) but here's a quick summary of the two.

First, when people are doing "information" work, i.e. work that involves sharing knowledge and information, they're doing three main things:

- Collaborating – having discussions, asking questions, giving feedback, chating, sharing files, and so on

- Collating – keeping conversations connected, delineated, and linked to a

topic in order to help maintain both content and context. - Orchestrating – ensuring people see, understand, acknowledge, or

address conversations and topics, and helping others have a higher-level sense of what conversations or topics they should follow and participate in.

Second, a single communication type – like IRC-style chat – cannot encompass all the communication needs a person has at work. If you're familiar with the Eisenhower Matrix, I used something similar. Mine was about the different types of communication that happen at work, and went like this:

- Important and ephemeral – the question is addressed or problem is being solved in real time

- Important and not ephemeral – something you absolutely need to see but not urgently

- Not important and ephemeral – free pizza at someone's desk (ok, sort of important)

- Not important and not ephemeral – fun but still valuable stuff that's a bit more evergreen, usually shared in social channels

Third, or maybe 2b, not all of the above can be completely communicated via chat. Some of them might need a Google Doc with comments. Some might be more of a living document in the form of a wiki. Some might unfortunately require an email.

Finally, there is what I call "the 100 inboxes problem." At work, this means that everything that used to come to your one email inbox and maybe an internal bulletin board now shows up in any one of 100 channels and direct messages, all of which are organized by various people, if they're organized at all, and all of which are hierarchically at similar levels when it comes to importance and urgency. (Note: This was years before Slack rolled out additional tools to help people better prioritize and organize, so maybe it's better now.) Stuff could be anywhere! And if you were an admin assistant, your job was 10x harder than everyone else's!

You can hopefully see how all this applies to social media and the news. If you are like me, your shit is just everywhere: Bluesky, Apple News app, maybe a few publications I still like, countless newsletters on various platforms, other social media, texts, god knows what else. Everything is on fire, and everyone is dialed up to level 11. No comment section is safe, no Reddit thread immune. We are all so tired. Honestly, I would like to escape the news for a day. At the very least I would like to more effectively calibrate it, control the intensity and the frequency without having to choose between "mute" and "full blast."

More than that, though, we are so stuck in the artificial constraints of these various platforms that we don't think about how those constraints might actually be contributing to the problem. Sure, we know that a bullshit attention grabbing headline will get someone more clicks, and we hate it – so why do still reward it by clicking? Sure, we know that short-form social media posts leave little room for nuance, so why do we not click through to the article, or insist on doing long threads, or argue with each other in bad faith bite-sized chunks? Of course nuance and complexity is lost. A tweet or a Bluesky post is not designed for either one. That's not what they're for, so why do we keep trying to use them for topics that could benefit from more of both things? Where do we have the space to engage in it with one another, rather than sniping back and forth at each other?

There has to be some kind of shift. Platforms cannot dictate how and in what form we share information. We – the people who make products – have to think about more human-sized spaces and human-friendly tools, because the current batch doesn't allow us to effectively navigate the relentless shitstorm of 21st Century life without losing our minds and/or bludgeoning each other.

But we – the people who use the products – also have to be willing to do some work too. We have to find ways to expand back into nuance, which requires more than 240 or 300 characters. We have to allow for doubt and reconsideration, and we have to do more than getting mad, whether at Them or at the Us that isn't us-ing correctly. We definitely need to come up with more actionable insights than "when you don't check the news as much, you're not as aware of the news." Sorry.

Until next Wednesday.

Lx

PS - If you missed it, the fine fellows at the Basic AF podcast invited me to join them, and I had a great time. Please listen and tell me what you think!

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.