Beyond the Valley of the Douchebags

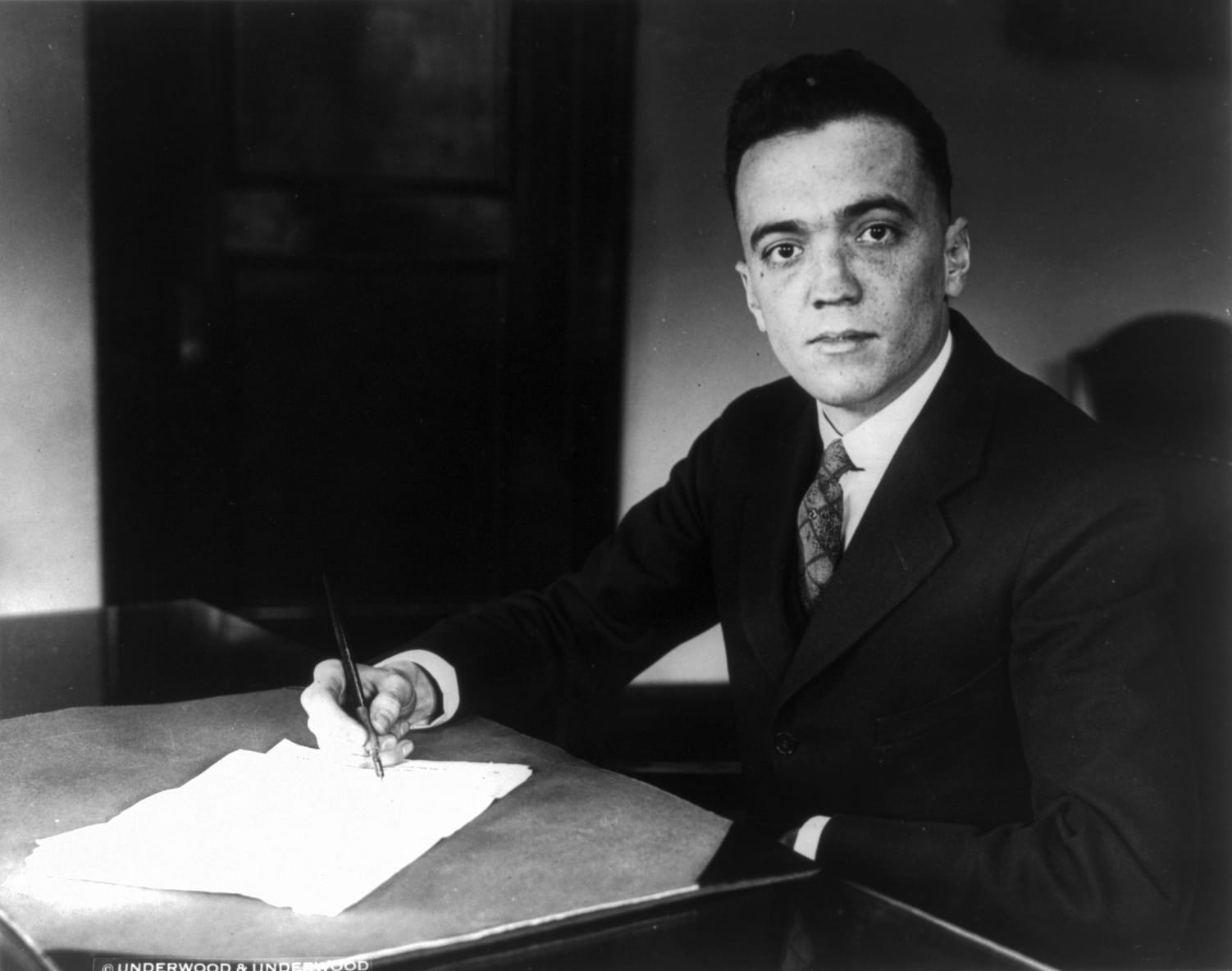

At the end of 2023, a friend of mine texted to ask me, "Do you like biographies? I just read the most incredible biography of J. Edgar Hoover." It says a lot about our friendship that I didn't immediately laugh at this confession, because that hasn't always been my experience when I've recommended the same book since. But coming from this friend, the recommendation carried a lot of extra weight, so I thought, what the hell and began listening to G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century by Beverly Gage.

Before this, if you'd asked me about Hoover, I wouldn't have been able to tell you much. I knew some of the big points like COINTELPRO and his lifelong desire to eradicate communism. After all, my grandfather had been blacklisted in the 1950s. Beyond that? My entire perception of the man was that he was a total bad guy, absolutely evil, might have dressed in women's clothing, the end. I don't know whether I wanted to know more than that, or whether even I thought there was more to know.

So you can imagine how surprised I was when, 36 hours of audiobook later, I found myself wishing I could spend more time with J. Edgar Hoover. Not because I liked him or suddenly admired him – quite the opposite. Definitely not a good guy! But a fascinating one, who did something pretty extraordinary in maintaining so much power for such a long time. I loved learning just how stupidly simple my narrative about him had been, and how entirely incomplete. I loved how the book forced me to complicate my understanding of him, both as an individual and as a powerful historical figure. It's uncomfortable to think of someone like Hoover as an actual person, a human being who may have had (deep breath) some good qualities and occasional good intent. I loved learning how my simple narrative of the Big Bad Guy Who Did All the Bad Things elided the much bigger truth: No one can attain, let alone maintain, that level of power without the support of a vast system of other individuals and institutions, many of whom are looking to get something in return.

There are few things as powerful as a simple, clear narrative. You can see this everywhere, in movies, novels, business, and politics. You can even see it in personal relationships. Black and white, good versus evil, the hero and the villain, the one bad guy and the rest of us who suffer or the one good guy and the world out to destroy him. Why else has Star Wars had such a chokehold on popular culture for the past five decades? The ultimate hero's journey, in which Luke's costumes literally represent his innocence (all white) and his battles with the dark side (all black).

Simple narratives are also powerful because we rarely stop to question them. Why would we? Life is busy and complicated enough. And anyway, some simple narratives seem sufficient in themselves. Do I really need to know more about why someone is a power-hungry monster if knowing more won't change the outcome of his behavior or how it affects me? Do I really need to understand the inner workings of an organization if there's nothing I can do about it and if, again, the outcome is the same? Do I really need to know whether the bad guy was facilitated by a whole system of not-so-bad guys, and that even people I might have supported or admired occasionally worked with him and helped him achieve his goals? Really, what difference does it make to know a more complex narrative when knowing it has zero effect on the end result, which is that some powerful asshole made a decision, and that decision fucked things up for a lot of people?

It's a fair argument. I've had it with friends, and even with myself. I know as well as anyone that in everything most of us face there is often a vast, perhaps even insurmountable power differential. In some ways, the simple narrative is the only power we might have, the only way we can stick it to an actual bad guy. Sure, he had all that power, or all that money, or both, but his comeuppance is a public evisceration. The long arc of justice bends our way just a smidge when history primarily remembers him as an asshole.

But somehow that's not enough for me. It's satisfying in the moment, but then what? What happens next if nothing changes? My life is still the same. If anything, it's marginally worse because I know someone else is out there finding new ways to ruin our lives. And eventually I'll learn there were a whole bunch of people who should have had it coming, but they all escaped notice unscathed. Like...that's it? There's nothing I can do or have control over?

Unless you've been living under a rock, you've probably guessed that this newsletter was nominally inspired by Careless People, the new tech tell-all memoir written by a one-time Facebook policy director. Honestly, judging by my texts and socials, you may have even read it. I haven't read it yet (although I will), so I can't say anything about the book itself, and this newsletter isn't really about the book, per se. Just that the book and the reaction to it has me thinking. First, of course, what a colossal self-own this has been on Meta's behalf. I can guarantee you that many of the people reading it now would never have heard about it, let alone rushed out to read it, let alone pushed it to #1 on Amazon and the NYT best seller list, had Meta not actively tried to block its distribution and promotion, which in this very specific current moment, helped create an absolute frenzy. People are absolutely primed to go feral on Mark Zuckerberg right now. If there were ever a time for Meta to not shine a spotlight on a memoir like this, it would be now, but I guess that's one thing this memoir, as with others, wants to remind us: These people are so controlling and manipulative and obsessed with their own self-image and pursuit of power that they literally cannot care about anything else, not even about whether that obsession might also come back to haunt them.

God, I used to be worried when writing about Instagram and Meta, because you never know what might cause them to pursue legal action. Now I can only dream of it, for the publicity alone. And for what it's worth, I feel confident saying all this if only because I reviewed a similarly dishy tech memoir by a woman who worked at Amazon for 12 years, under the equally-reviled Jeff Bezos, and that book did not have quite the impact this Meta memoir is having. In fact, I bet the majority of you are hearing about it here for the first time.

Anyway, I do not want to imply that this book has no merits or wouldn't have been successful on its own. I don't know! I should probably have read it before I wrote this newsletter! But whatever, I didn't want to write about the book itself, or even about whistleblowers and tell-all memoirs. That's often – usually! – important work. I've even discussed this in a past newsletter. People learned a lot when Frances Haugen unleashed the Instagram Papers (and more) in 2022, about how much Instagram knew about harm the product does to teen girls. They should know about that, and they should be angry about it. Same goes for whatever this memoir reveals about the many horrible political and economic implications of Facebook's, Mark Zuckerberg's, and Sheryl Sandberg's many missteps.

Like most everyone, I want to know the details. I'll read it, and I'm sure I'll be interested. But what I will be more interested in is the narrative. Not just the narrative of the book, but the narrative that surrounds it. How many times can we be angry at someone so beyond our sphere of influence? How many stories of greed, ruthlessness, corruption, pursuit of power, world domination, and devastation can we consume? What does it mean that we keep consuming them and that we keep being surprised at the revelations? People love to remind us that "absolute power corrupts absolutely" and then are shocked to discover that someone is doing whatever it takes to maintain that position.

Sometimes I wonder if we like tell-all memoirs only because we want to watch someone stick it to a powerful asshole, or if secretly we feel relieved that we don’t have to ask ourselves how we contribute to the larger problem, or whether we would have behaved differently if it had been us.

You're probably looking at me like I have lost my goddamn mind. How do any of us contribute to the problem of Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook enabling a genocide in Myanmar? Obviously none of us do. But what do we do that might in some way enable Mark Zuckerberg to even be in this position? What problems did and do we overlook to continue using his products? What do we ignore or accept for our own ease and convenience? What behaviors do we excuse or even reward, what problems do we ignore, what tradeoffs have we made in our lives, relationships, jobs that also contribute to a culture in which any of this shit can happen? Powerful corporations convinced all of us to stop littering and to start recycling our single use plastic, all while causing environmental devastation in ways powerless individuals cannot even fathom. But does that mean we shouldn't think, as individuals, about our own environmental footprints? Doesn't that also mean we should be a little more prepared when yet another industry – one known for creating products that cause harm as much as they might benefit us – unleashes a technology like GenAI whose environmental footprint makes the ExxonValdez oil spill look like a little bit of garbage on a highway median?

This complicated narrative is the one I am most interested in. How does a person like J. Edgar Hoover come into existence and then into power? How do the systems shape and facilitate him? How do people fall in line, or even bend their own lines to enable him? How do supposed "good guys" make bargains with him, so that something beneficial can happen, even if the cost is something else that's not?

Lately I've been thinking again about the concept called the "normalization of deviance," originally coined by sociologist Diane Vaughan:

the process in which deviance from correct or proper behavior or rule becomes culturally normalized.

Vaughan defines the process where a clearly unsafe practice becomes considered normal if it does not immediately cause a catastrophe: "a long incubation period [before a final disaster] with early warning signs that were either misinterpreted, ignored or missed completely".

Vaughan most famously used this in an analysis of the Challenger disaster, but I find it a useful concept in other areas too. If you have a hard and fast rule but you allow for a little wiggle room in applying that rule, what will you do the next time if nothing bad happens when you make this slight exception? Will you stick with the original version of your hard and fast rule, or will you now apply the less strict version? Over time, how much do you shift, and how will you avoid catastrophe?

I ask all of this in part because I myself took the money. If I'm really honest, can I even say that my job at Instagram was the first time I took money from a company that had done harm to people? I can't even say with confidence that I would have the willpower to resign. I'd like to think I would, but who knows? After all, didn't I choose to work? I recognize how much I normalized the deviance away from my own ideals, my own ethics. I tried to justify all the means for the perceived ends, but can that really be justified?

This may be normal human behavior that's hard to avoid, especially in a society rife with inequity and vast power differentials. It's hard not to fall into the trap of "sorry everyone else, but I need to get mine" when it's offered to you. Who has the luxury of opting out of this whole shitty system? And yet, if we never stop to complicate the narrative and ask what where we might be complicit, are these tell-all memoirs really anything more than a brief diversion, an outlet for outrage, and sad glimpse of what might have been?

It is very hard to enact change, whether inside an organization or out. I don't know that our culture can change, but I think it inevitably will, because that's what cultures do. They're not static. Like many people at these companies, I tried to push for change when I could. The puny results of my efforts were pale imitations that took months, maybe years, to even see the light of day, but they were something. The most effective effort was the one in which I wasn't pushing alone. Most of us have allowed our rules to be eroded bit by bit, year after year, yes after yes. Maybe there's collective power in this, too.

Until next Wednesday!

Lx

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.